Authored by Blake Sherry

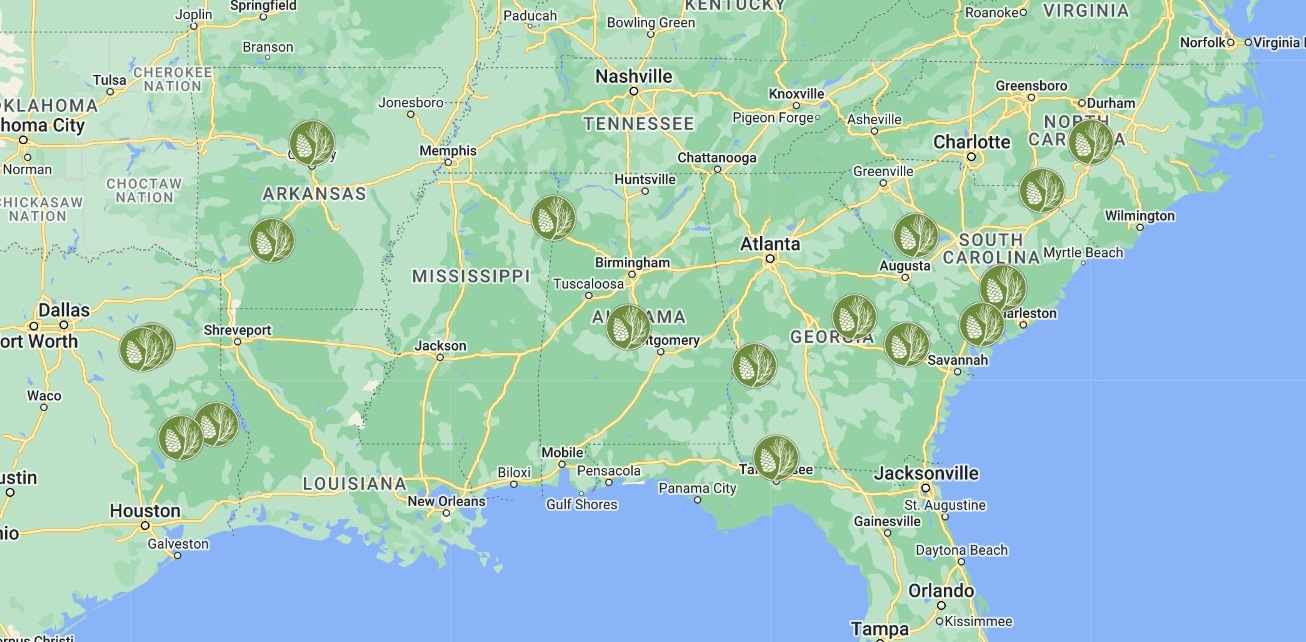

Blake Sherry is the Reforestation Advisor for Florida, Southern Georgia, and Southern Alabama.

Blake has been a valuable member of the ArborGen team since September 2024. Before joining ArborGen, Blake was a Procurement Forester for over five years.

The fundamental question in forest management we often seek to answer is: What is your primary objective? For most landowners I talk to, the answer is primarily to seek the highest return on their investment, while promoting recreational opportunities like hunting and maintaining all the society-enhancing benefits that forests provide.

Twenty years ago, “plant it thick and cut it quick” was the highest-returning management regime, summed up in a catchphrase. No matter how that volume was distributed across the stems, tons per acre were all the paper mill needed—and the paper mill was king. But now, in our current and most likely future markets, focusing site nutrients on the stems that will become sawtimber seems to make the most sense.

When a landowner decreases the trees per acre (TPA) at planting and increases the potential of each tree to become a higher-value product, they not only increase the tract’s value at harvest but also advance the harvest time by a measurable amount. Many worry that their stand will not reach the necessary height to meet merchantable product classes when they reduce planting densities. This is a prudent concern, but one we’ve found to be less of an issue than previously thought, for two reasons: one, a tree’s height growth is less affected by reduced spacing than its diameter growth; and two, sawmills do not need logs as long as you might think.

Recently, we collected data from a demonstration plot entering its ninth growing season. It was planted with MCP® and OP families at 436 TPA and 622 TPA. In total height, the OP families planted at 436 TPA were 1.9% taller than those planted at 622 TPA. For the MCP® families, trees were only 1.2% taller at 622 TPA than at 436 TPA. The most significant difference came in diameter: OP families were 4.8% larger in Diameter at Breast Height (DBH) when planted at 436 TPA vs. 622 TPA. At the same time, MCP® families were 16.3% larger in DBH at the lower density.

MCP-Elite planted at 454 TPA, age 6.

OP-Elite planted at 454 TPA, age 14.

If a landowner is trying to get sawtimber-sized trees to market sooner, most would agree that trading 1.2% in height for a 16.3% increase in diameter is a worthwhile exchange.

Another reason the diameter matters more is that most sawmills do not need logs as long as your might think. Many sawmills have specifications for logs in the 10- to 20-foot range, with some defining a “tree-length” log as short as 25 or 33 feet. When a log is processed at a mill, the first step is to buck it into optimal lengths, typically between eight and twenty feet, to maximize efficiency and product output. Depending on the sawmill’s configuration, shorter logs may even command a premium, as they reduce the amount of on-site processing needed.

Sawmill in Georgia with at least a quarter of the yard dedicated to short log storage.

Diameter growth has the most room for improvement when you reduce planting density, as height growth tends to come with a well-stocked stand. Just be mindful: To realize the value of lower planting density, you must use the best genetics available. The benefit of reducing density is only fully realized with a tree with strong inherent sawtimber and growth potential. Reducing planting density with a tree that yields the same pulpwood volume regardless of spacing is a step away from achieving most landowners’ financial objectives.